For water is indeed the resource upon which the foundations of the future will stay afloat

History bears testimony to the fact that the process of siting of settlements has often been determined by two factors—the advantage of altitude for better defence and availability of water to sustain food production and trade. Ganga is a prominent example of the latter, and it has witnessed the rise and fall of many big and small kingdoms throughout history.

It has been one of the most important rivers not only of the subcontinent but of the world as well, both from an ecological and a cultural point of view. Not only has it nourished a civilization with a constant supply of water, but on various occasions it has helped in controlling floods and maintaining the ecological balance. Thus, it can be said to have offered several provisioning, regulating and supporting ecosystem services.

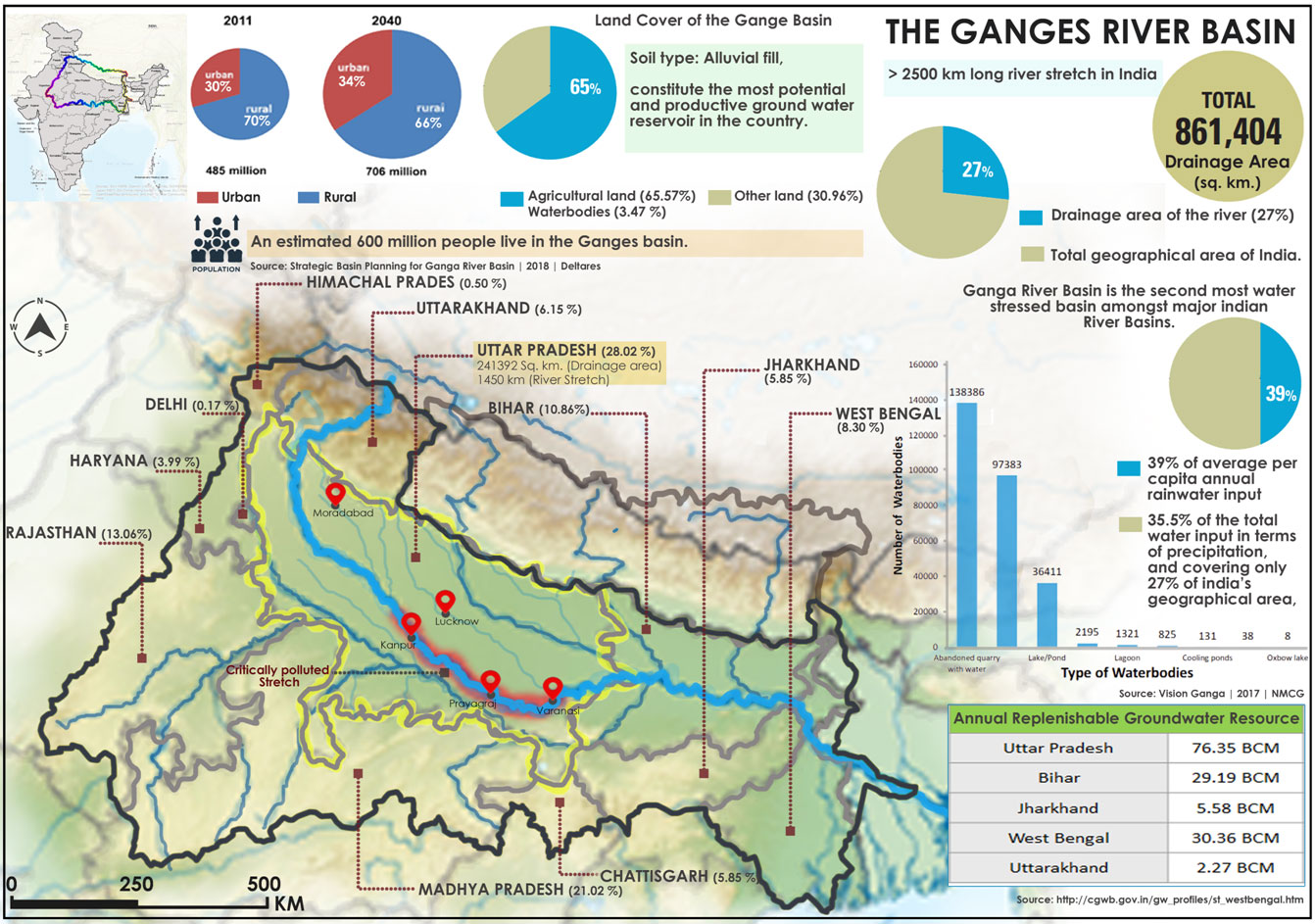

In the present context, Ganga continues to be the spine within the urban landscapes of the cities it flows through. Ganga basin has 2,009 statutory towns, with an urban population of 165.2 million (16.52 crore), as per Census of India 2011. It is perceived to be sacred by a vast percentage of the Indian population and also provides various socio-economic benefits to the citizens in being a space that stimulates societal interaction and improved health. Moreover, it helps keep at bay the effects of climate change to some extent by mitigating the urban heat island effect and flash floods that these urban areas have been wont to experience.

However, in recent years, the river has been facing the brunt of the rapidly rising tide of urbanizationin the country. As cities grow exponentially, their water sources are stretched to their limits. Rivers are being overexploited and polluted by industries and agricultural runoff, their natural course is being modified in order to make way for modern developments and the hydrological cycle itself is being inadvertently interrupted which leads to cases of severe water scarcity in most cities.

A comparative view of the decadal fluctuation of post-monsoon GW levels from 2009–19 shows that there is considerable deterioration in Uttarakhand, western and northern Uttar Pradesh and parts of Haryana and Rajasthan. These areas have witnessed GW levels dropping from 5–10 metre below ground level (m b.g.l.) in 2009 to 20–40 m b.g.l. There is extreme GW stress with depleting GW table, and most urban areas in the basin are categorized as ‘over-exploited, critical and semi-critical’.

It is now more imperative than ever that we turn our attention to the condition of rivers like Ganga, and acknowledge the damage that we have brought upon them. India is going to continue to urbanize, so a course correction in our policy and practices regarding our rivers can be the difference between their death and thriving revival.